History

Section overview

Falcarragh and World War I - Jack and Tom McGinley’s family history, their upbringing and schooling in Donegal, tea training in London, and founding of the company in Derry in 1928.

Opening Foyle Street - Establishment of 12 Foyle Street office in 1930 and tea sourcing from India.

Economic War - Impact of the 1930s economic war between Ireland and the UK, the establishment of new trade links, and a second premises in Bridgend, Donegal.

World War II - Navigation of WWII, rationing on both sides of the border, and continuing economic war with the UK.

A new office and The Troubles - Growth of the family business, establishment of new offices at 12 William Street, and the start of The Troubles.

Conflict escalates and a fire - Escalating sectarian violence in Derry, a fire guts the William Street office in 1971, and the business’s closure in 1976.

Falcarragh and World War I

Just before her 20th birthday, Gertrude Rudden married Patrick McGinley, five years her senior, at St. Chad’s Catholic church in central Manchester. Cheetham Hill, the neighbourhood where Gertrude had grown up, had been a refuge from famine in the mid-1800s for many Irish immigrants. Patrick was from Falcarrgah, a small Gaelic-speaking town in northern Donegal, but had been working as a bank cashier in Armagh. After their wedding in 1902 they moved to Falcarragh, and he took over management of the family store. By the time Gertrude turned 35 in 1915, she had given birth to 10 children.

The year after Nora, their tenth child, was born, Patrick died of a heart attack at age 41. Later in life, Jack, their second, who was then 13, said he cried for two weeks when he lost his father. At only 37, Gertrude was now alone with ten children still at home to take care of. The eldest, Maureen, had started boarding school in England but Gertrude had also taken responsibility to raise a nephew, Noel. Soon after Patrick’s death, Gertrude sent Jack and Tom to boarding school as well, 30 miles away at St. Eunan’s in Letterkenny.

When Patrick died in 1917, World War I had been raging on continental Europe for three years. Ireland was still part of the United Kingdom, and although there was never any fighting on Irish soil, German submarines patrolled the Irish Sea. So when Maureen, at 14, returned by boat from boarding school for her father’s funeral, the move was permanent. She finished secondary school outside Dublin.

Shortly before he died, Patrick wrote to Maureen congratulating her on good grades but also reporting that her uncle Tom was shortly off for the front. Poor chap, I do not envy him his mission and fear the war is far from over. Tom lived in Manchester, and Englishmen between the ages of 18 and 40 were obliged to fight. Although there was never mandatory conscription in Ireland, an estimated 200,000 Irish, both Nationalists and Unionists, fought with the Allied powers. Tom survived. Some 40,000 to 50,000 Irish soldiers did not.

In the same letter, Patrick also wrote to Maureen about her brothers Jack and Tom. They had become avid fishermen. No sooner are they home from school, have their dinner over and practicing done than they are off to the river, Patrick wrote. He also mentioned Jack’s remarkably fine touch on the piano.

Although the McGinley children were able to live relatively normal lives in Donegal, in spite of the war, it was also a time of major political change in Ireland. The republican movement was gaining strength and was, in part due to World War I, starting to have better access to weapons. In 1922, three years after the Irish War of Independence had begun, the UK and Ireland signed a partition agreement, and the island was split into Northern Ireland, which remained part of the UK, and the Irish Free State.

Jack had just started attending St. Eunan’s when WWI was ending and stayed at boarding school through the Spanish Flu, the War of Independence, and until after Partition. He graduated in 1922 and the following year moved to Derry, now in a separate country, to start a job as an assistant at Alexander McCay, a grocer on Ferryquay Street. On his way to Derry, he would have passed, for the first time, new customs offices on the border.

McCay’s was a wholesale grocers supplier but they also blended and sold tea, and Jack worked in the tea department. After almost four years in Derry, McCay’s supported him to move to London in 1928 for a year-long apprenticeship at Appleton Machin & Smiles, a large tea company on Bankside, where he learned tea tasting and blending. When he returned to Derry he and Tom rented an office in Commercial Buildings on Foyle Street and incorporated J&T McGinley, their own small tea company, using their savings and a small loan from their uncle Dan McGinley. Jack and Tom were only 24 and 22 years old, but like many young people at the time, they had grown up quickly.

Opening Foyle Street

J&T began as a small-scale supplier of loose, unbranded tea and it wasn’t until two decades later that they began selling under their own label, initially called Gold Cup. Derry was already a competitive tea market in the 1920s, and Jack’s former boss Alexander McCay had warned him away from what he described as a ‘dog-eat-dog trade’, as a family member would later recall.

But the company got off to a strong start, and two years after opening they were ready to expand. They moved into a larger office at 12 Foyle Street, where they ran the administrative office but also sampled (‘cupped’), blended, and packaged their tea. Grocers throughout the city sold their blends. Number 12 Foyle Street remained the J&T office for the next 35 years.

There were times that Jack supplemented the tea trade with sales of other products, including beer and coffee (a short-lived side line). This pragmatism, together with his commitment to quality and the fact that he was well known and liked, helped the business to prosper where many others failed. Thirty years after the company opened, the number of tea companies in Derry had reduced from around twenty to only a few; J&T had become one of the only remaining tea business ‘west of the Bann’, a river that bisects Northern Ireland.

For most of the first two decades of operation, the tea came exclusively from India, still a British colony at the time. Indian black tea was mostly produced on British-run estates in Assam, where it would be rolled, fermented, dried, and loaded into wooden crates bearing the mark of the plantation. After processing, the tea was transported by road to trains and boats that carried the valuable cargo the rest of the thousand mile journey to Kolkata (formerly Calcutta). From there, it took a month by steam ship to travel around the tip of India, through the Suez Canal and the Strait of Gibraltar, and north to the UK.

The majority of the company’s tea – and a third of the global tea trade at the time [1] – initially came through the London Tea Auction on Mincing Lane.

Economic War

In the mid-1930s, partly in response to the Great Depression and partly because of a dispute with the UK, Ireland began heavily taxing goods imported from Britain. This made it uneconomical to continue selling tea from the Derry office into the Irish Free State, so Jack and Tom established a second premises in Bridgend, just over the border in Donegal and only four miles from Foyle Street. Running this parallel operation, which, due to the new trade laws had to have a separate supply chain, was time consuming and costly. Although this additional expense would have frustrated the brothers, the Irish supply chain would prove valuable in just a few years with the start of WWII.

At the end of 1938, 10 years after they had opened the first office in Commercial Buildings, Tom left the company to pursue a new business interest. Around the same time, their sister Bridie joined as an administrator and continued working at J&T for two decades. Tom also would later return to J&T – which the brothers agreed would keep its name – in a sales position. His departure and Bridie’s arrival was at the start of what would be a major period of change for the company and coincided with increasing inevitability of war in Europe.

World War II

Despite Ireland’s drive to become more economically self-sufficient in the 1930s, it remained dependent on Britain for both shipping and trade. In the run-up to WWII, the Irish government wanted to establish a national six-month stock of key commodities, including tea. They approached the Irish Wholesale Tea Dealers’ Association, of which Jack was a member, about creating a buffer stock, but the association rejected the proposal because of the high cost to its member businesses. This decision would have been partially informed by confidence in Ireland and elsewhere that France and Britain would quickly win the war and the impact on the economy would be minimal[2].

This confidence was of course misplaced, to devastating effect for both Ireland and the UK. Supply of goods became increasingly restricted throughout the war, and both countries had to impose rationing. To preserve its own stocks, in 1941 the UK abruptly cut tea exports to Ireland by seventy-five percent.[3] Prior to this, the vast majority of Ireland’s tea supply chain came through the London auction. Reflecting the seriousness with which the shortage was viewed by the public, between 1941 and 1942 the Irish government directly purchased 12 million lbs of tea in Calcutta to ship to Ireland. The shipment took a convoluted journey through the Panama Canal, New York, and Montreal to avoid the battleships deployed to fight the war.[4]

While the trade restrictions meant it was useful that J&T already had established supply chains on both sides of the border, tea rationing threatened the company’s finances. Britain and Ireland were the two biggest per capita tea consuming countries in the world, with a weekly consumption of close to three ounces per person.[5] [6] So when the UK instituted a two-ounce ration, it could have reduced J&T’s tea sales by up to a third in Derry, its biggest market. Ireland’s significantly more austere rationing, which went as low as half a ounce per person per week, could have also reduced sales in Donegal by up to 80 percent. The negative impact of the ration sizes on the business were offset in part through higher prices and support from the Irish government on rationing [7].

The company also offset losses by launching a new division, opened in 1938, as an agent for beer made by the Scottish brewer William Youngers.[8] Both Canada and the United States had set up military bases in Derry during the war, and the soldiers’ relatively good salaries kept pubs busy and that meant that beer became a significant side line for the company for a period.

J&T also made a brief foray during the war into coffee sales. Due to the tea shortage, coffee consumption in Ireland increased from 672,000 lbs annually to over 4.5 million lbs in 1942. Demand for coffee quickly subsided again when tea availability improved, evidence of the importance of tea in Ireland.[9]

A new office and The Troubles

In 1941 Jack met Agnes Burke, the youngest child of ten from a family of bacon producers in Clonmel, County Tipperary, at a dinner at the Gresham Hotel in Dublin. They were married the following year by Jack’s uncle, the Reverend Canon Dan McGinley, who had presided over Patrick and Gertrude’s wedding a generation before and had also given Jack and Tom the initial small loan to start J&T. Agnes gave birth to their first child, Rosemary (Rosie) in 1943, followed by Patricia, John, Oonagh, and in 1949 twins, Denis and Patrick. Like his father, John would also apprentice at Appleton Machin & Smiles in London and joined the business in 1968. Two years later, Patrick would also join after a tea training in London.

The 25 years between the end of WWII and The Troubles was a period of prosperity for the company. The tea ration continued in Northern Ireland until 1952 but then the market fully rebounded[10]. J&T expanded tea sales throughout Northern Ireland and kept the beer business running.

The brand name Gold Cup was adopted in the late 1940s, but it was short lived because a Belfast-based company trademarked the name. Jack came up with Goalpak in 1954 and took out announcements in newspapers notifying customers of the change[11]. Goalpak introduced red, yellow, blue, and green label teas. Red was the premium label and had the highest proportion of top quality tea. Yellow was the most popular, constituting approximately 90% of sales.

Jack was in charge of making the selection of teas from various estates – which, after the war, expanded to include tea from Ceylon and East Africa – a skill he handed down to John and Patrick when they entered the business in the late-1960s. In Ireland, full-bodied African teas grew in popularity after WWII and became a feature of many Irish teas. A single blend of Goalpak could contain tea from more than 10 different estates, balanced to suit the peaty water used to brew tea in north-west Ireland.

J&T got their tea samples from large wholesalers in London, who posted taster packages to Derry. Jack, and later John and Patrick, would sample them and then have the option to bid on a lot, which could contain tens of thousands of pounds of tea. If they won the bid, the tea was shipped directly from the plantations, a process that would often take three months from start to finish.

In the 1960s, Guy’s, a Cork-based company, redesigned Goalpak’s branding and created packaging that the tea would become known by. The bags had calligraphic black vertical text and a large logo of a tea pot with a historical depiction of soldiers at camp.

At its peak in the late 1960s and early 1970s, J&T employed 25 people and sold close to half a million pounds of tea a year. To meet this demand, they invested in new infrastructure to warehouse, blend, and package. Realising one of Jack’s lifelong dreams to own his own office and warehouse, he bought a property at 96 William Street in Derry’s Bogside neighbourhood in 1966. It was a beautiful neoclassical building with tall archways, standing on the corner of William and Abbey Streets, the former office of Watt distillery that had once been the largest whiskey producer in Ireland and among the largest whiskey sellers in the United States[12].

Jack always gave opportunity to family members to work in the business. His sister, Bridie, ran the accounts for over twenty years, Tom had reentered the company to focus on sales, and their cousin, Noel, who was raised as part of their family, worked in the warehouse. After a bachelors degree in commerce at University College Dublin and tea training in London, John joined the business in 1968, increasingly taking a leadership role through the 1970s. Patrick joined two years after John and worked alongside Jack and John in sales.

After two decades of relative prosperity, the fortune of the company began to turn — the timing of the move to the new office in William Street was bad. At the time J&T moved into the new property the Bogside was calm, but two years later tension had reached a breaking point. On 5 October 1968, Catholic civil rights marchers clashed with Protestant counter-protesters and the police, an event that marked the start of The Troubles in Derry.

Conflict escalates and a fire

In August 1969, less than a year after the initial clash, and three years after J&T’s move to William St., fighting shook the city for three days in what came to be known as the Battle of the Bogside. News of the violence led to sectarian clashes throughout Northern Ireland, and the British government deployed the army to restore control. Much of the fighting in Derry took place on and around William Street. While J&T mostly stayed open, it had to operate with its windows boarded up.

The unrest had direct impact on J&T’s day-to-day operations. Looters frequently made off with product from the William Street property. On one summer night in 1970, 240 bottles of beer were stolen to make petrol bombs. The company had to be very deliberate about protecting its neutrality during the conflict.

In 1971 Jack and Agnes took an early-autumn trip to Spain. By this time they were in their mid-60s and had started annual holidays to mainland Europe. On the morning of September 21 they had just stepped out of a church in Majorca and were surprised to bump into John F. McLaughlin, a friend from Malin in northern Donegal. John began commiserating about the bad news he had received from Derry.

That was the first time that they had heard about the fire that had gutted the William Street premises two days before. During riots, protesters set fire to the building, as they had done to so many other businesses in the vicinity. The area had become lawless and the building had caught fire and been looted several times over the preceding two years. On the afternoon of September 19, however, the fire brigade was unable to extinguish the blaze.

During the two weeks prior to the fire, Derry had been particularly tense. On September 6, Annette McGavigan, a 14-year-old, was shot and killed by the British Army in the Bogside on her way home from school[13]. Then on the 14th, an IRA sniper shot and killed a British soldier, and the following day another Catholic civilian was shot while walking home[14]. These events set the scene for fierce rioting.

Even before Jack returned to Ireland, the building was deemed structurally unsound and had been levelled by one of several companies in Derry that had become specialised in tearing down fire-gutted buildings. John, Jack’s eldest son, drove him into Derry the day he got back from Spain. Jack was inconsolable when he saw the ruins. Unlike for the Watt distillery, which had been rebuilt on the same site after being gutted by a blaze in 1864, the security and economic environment was not conducive to re-establishing[15].

J&T eventually received a compensation pay out from the British government, and for a number of years Jack, John, and Patrick made an effort to rebuild the company. A new site had been purchased on the Pennyburn Industrial Estate in Derry, architects were engaged, a new building frame ordered. Ultimately, though, a decision was made to not proceed; there were economic challenges with operating in Derry at the time and safety of family and employees was also a significant consideration. Derry was Goalpak’s biggest market and it continued to be an epicentre of violence until the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1997.

Just four months after J&T was razed, one of the most significant days of The Troubles broke out further down William Street. On 30 January 1972, in an incident known as Bloody Sunday, British paratroopers shot 26 unarmed civilians who were protesting. Fourteen of them died[16].

In 1976 J&T McGinley shuttered permanently. Jack’s health deteriorated quickly after the company closed and he died three years later at 74. While John and Patrick attributed the fire to the general anarchy in the Bogside that summer, Jack believed the company he successfully built over five challenging decades had been targeted, and he took the loss to heart.

See references and comments box on About & Comments page.

Foyle Street, Derry (early-1900s)

J&T offices at 12 Foyle Street, Derry. To left of Taxis signage (1960s)

Google Street View image of Foyle Street (May 2017).

Gertrude (Rudden) McGinley, Maureen (standing) & Jack, 1905

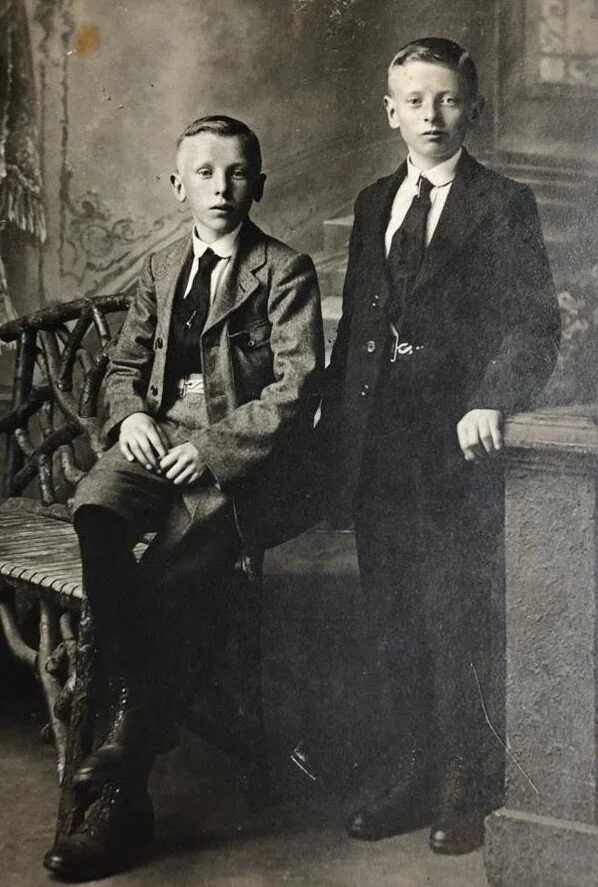

Tom and Jack McGinley (c. 1917)

Jack McGinley’s brass tea sample scales

Tom leaves the business. The Belfast Gazette, September 8, 1939

Jack, Rosemary and Agnes. 1944

A brief wartime sideline for J&T. Derry Journal. 4 September 1942

The Goalpak Tea brand is established. Derry Journal. 1 December 1954.

Falcarragh Show Day programme. 1964.

Goalpak Yellow (1970s)

Goalpak Red (1970s)

Derry Journal article on establishment of the new company headquarters. 14 January 1966. 96 William Street at Abbey Street.

Photo from Derry Journal. Monday, 29 June 1970: "Racing for cover from an army charge on William Street".

Google Streetview image (Jun 2020) of site of former J&T McGinley offices at 96 William St.

Jack McGinley’s obituary in the Derry Journal, 5 June 1979